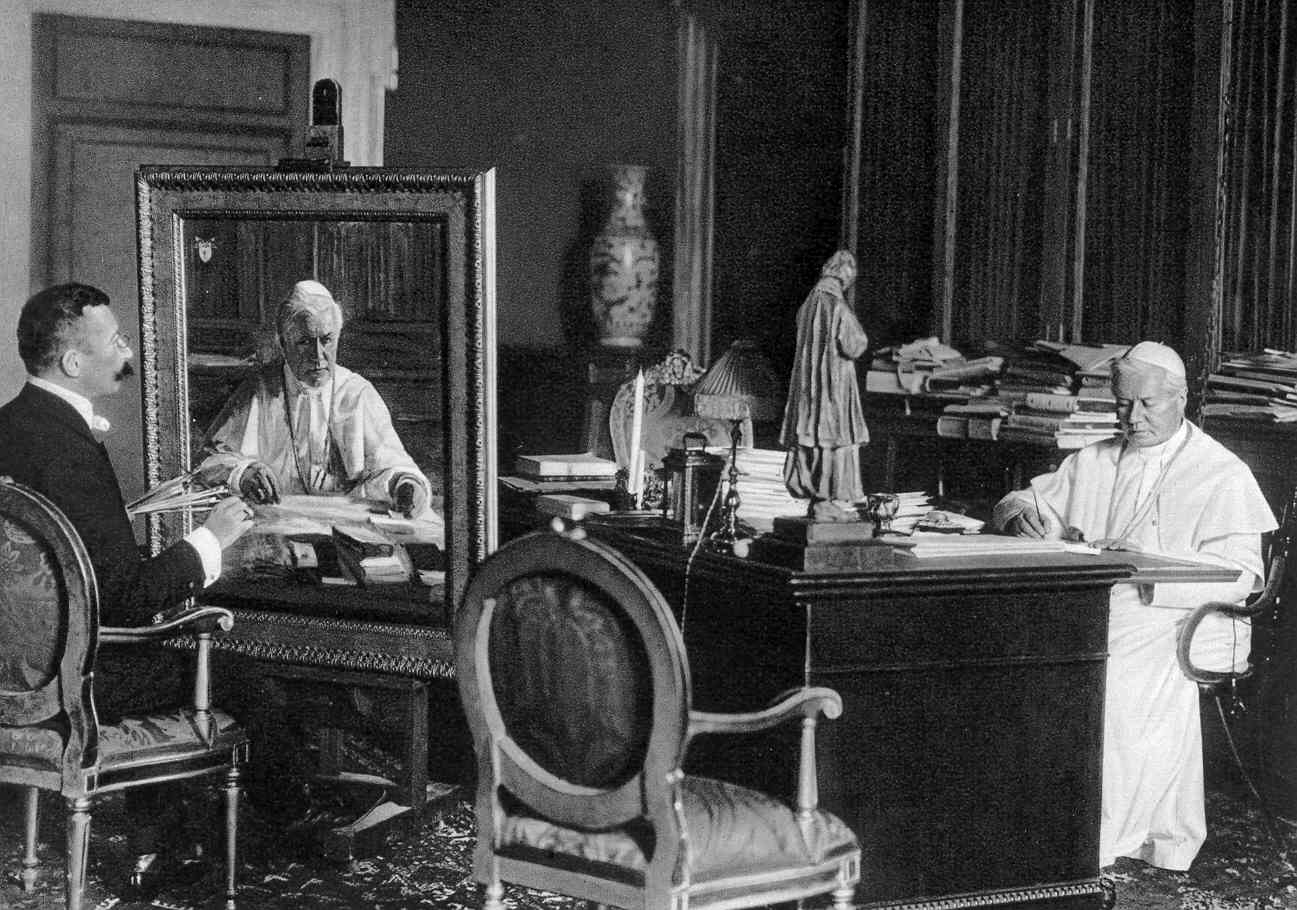

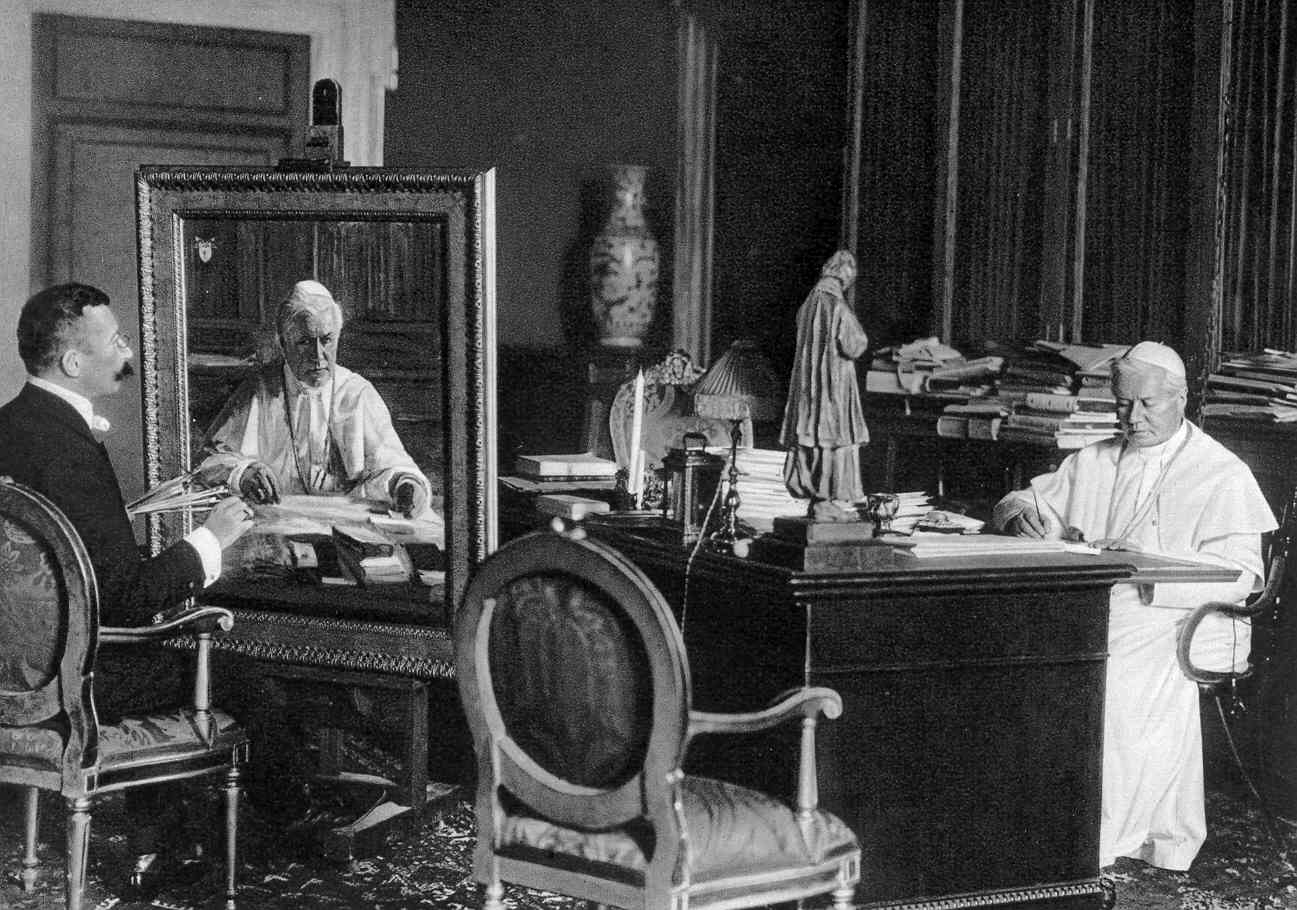

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing

modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

interpretations of

Catholic doctrine Catholic doctrine may refer to:

* Catholic theology

** Catholic moral theology

** Catholic Mariology

*Heresy in the Catholic Church

* Catholic social teaching

* Catholic liturgy

*Catholic Church and homosexuality

The Catholic Church broadly ...

, and for promoting liturgical reforms and scholastic theology. He initiated the preparation of the

1917 Code of Canon Law, the first comprehensive and systemic work of its kind. He is venerated as a

saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

in the Catholic Church and is the namesake of the

traditionalist Catholic

Traditionalist Catholicism is the set of beliefs, practices, customs, traditions, liturgical forms, devotions, and presentations of Catholic teaching that existed in the Catholic Church before the liberal reforms of the Second Vatican Council ( ...

Priestly Fraternity of Saint Pius X.

Pius X was devoted to the

Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

under the

title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

of

Our Lady of Confidence

Our Lady of Confidence, also known as La Madonna della Fiducia or Our Lady of Trust, is a venerated image of the Blessed Virgin Mary enshrined at the Lateran Basilica. The feast of Our Lady of Confidence falls on the last Saturday prior to Lent.

P ...

; while his papal

encyclical ''

Ad diem illum'' took on a sense of renewal that was reflected in the motto of his pontificate. He advanced the

Liturgical Movement

The Liturgical Movement was a 19th-century and 20th-century movement of scholarship for the reform of worship. It began in the Catholic Church and spread to many other Christian churches including the Anglican Communion, Lutheran and some other Pro ...

by formulating the principle of ''participatio actuosa'' (active participation of the faithful) in his

motu proprio

In law, ''motu proprio'' (Latin for "on his own impulse") describes an official act taken without a formal request from another party. Some jurisdictions use the term ''sua sponte'' for the same concept.

In Catholic canon law, it refers to a ...

, ''

Tra le sollecitudini

''Tra le sollecitudini'' (Italian for "among the concerns") was a motu proprio issued 22 November 1903 by Pope Pius X that detailed regulations for the performance of music in the Roman Catholic Church. The title is taken from the opening phrase ...

'' (1903). He encouraged the frequent reception of

Holy Communion, and he lowered the age for

First Communion, which became a lasting innovation of his papacy.

Like his predecessors, he promoted

Thomism

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school that arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church. In philosophy, Aquinas' disputed questions ...

as the principal philosophical method to be taught in Catholic institutions. He vehemently opposed various nineteenth-century philosophies which he viewed as an intrusion of secular errors incompatible with

Catholic dogma

A dogma of the Catholic Church is defined as "a truth revealed by God, which the magisterium of the Church declared as binding." The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' states:

Dogma can also pertain to the collective body of the church's d ...

, especially

modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

, which he critiqued as the synthesis of every

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

.

Pius X was known for his firm demeanour and sense of personal poverty, reflected by his membership of the

Third Order of Saint Francis

The Third Order of Saint Francis is a third order in the Franciscan tradition of Christianity, founded by the medieval Catholic Church in Italy, Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi.

The preaching of Francis and his disciples caused many ma ...

. He regularly gave

sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. ...

s from the

pulpit, a rare practice at the time. After the

1908 Messina earthquake he filled the

Apostolic Palace

The Apostolic Palace ( la, Palatium Apostolicum; it, Palazzo Apostolico) is the official residence of the pope, the head of the Catholic Church, located in Vatican City. It is also known as the Papal Palace, the Palace of the Vatican and t ...

with refugees, long before the Italian government acted. He rejected any kind of favours for his family, and his close relatives chose to remain in poverty, living near Rome.

[.] He also undertook a reform of the

Roman Curia with the

Apostolic Constitution ''Sapienti consilio'' in 1908.

After his death, a strong cult of devotion followed his reputation for piety and holiness. He was

beatified

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their nam ...

in 1951 and

canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

in 1954 by

Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

.

A statue bearing his name stands within

St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

; and his birth town was renamed

Riese Pio X Riese may refer to:

*Project Riese, a German Nazi World War II economic project

*Riese Pio X, a municipality in Italy

* Adam Ries (1492–1559), German mathematician

*'' Riese: Kingdom Falling'' (originally named ''Riese''), an American science fic ...

after his death.

Early life and ministry

Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto was born in

Riese,

Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia

The Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia ( la, links=no, Regnum Langobardiae et Venetiae), commonly called the "Lombardo-Venetian Kingdom" ( it, links=no, Regno Lombardo-Veneto, german: links=no, Königreich Lombardo-Venetien), was a constituent land ...

,

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

(now in the

province of Treviso

The Province of Treviso ('' it, Provincia di Treviso'') is a province in the Veneto region of Italy. Its capital is the city of Treviso. The province is surrounded by Belluno in the north, Vicenza in the west, Padua in southwest, Venice in the so ...

,

Veneto

Veneto (, ; vec, Vèneto ) or Venetia is one of the 20 regions of Italy. Its population is about five million, ranking fourth in Italy. The region's capital is Venice while the biggest city is Verona.

Veneto was part of the Roman Empire unt ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

), in 1835. He was the second born of ten children of Giovanni Battista Sarto (1792–1852), the village

postman

A mail carrier, mailman, mailwoman, postal carrier, postman, postwoman, or letter carrier (in American English), sometimes colloquially known as a postie (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom), is an employee of a post ...

, and Margherita Sanson (1813–1894). He was baptised 3 June 1835. Though poor, his parents valued education, and Giuseppe walked to school each day.

Giuseppe had three brothers and six sisters: Giuseppe Sarto (born 1834; died after six days), Angelo Sarto (1837–1916), Teresa Parolin-Sarto (1839–1920), Rosa Sarto (1841–1913), Antonia Dei Bei-Sarto (1843–1917), Maria Sarto (1846–1930), Lucia Boschin-Sarto (1848–1924), Anna Sarto (1850–1926), Pietro Sarto (born 1852; died after six months). As Pope, he rejected any kind of favours for his family: his brother remained a postal clerk, his favourite nephew stayed on as village priest, and his three single sisters lived together close to poverty in Rome, in the same way as other people of humble background.

Giuseppe, often nicknamed as "Beppi" by his mother, possessed a sprightly disposition with his natural exuberance being so great that his teacher had to often control his lively impulses with a cane to the backside. Despite this, he was an excellent student who focused on his homework before engaging in any hobbies or recreations. In the evenings after sports or games with friends, he would spend ten minutes in prayer before returning home.

Sarto also served as an altar boy. By the age of ten, he had completed the two elementary classes of his village school, as well as Latin study with a local priest; henceforth Sarto had to walk four miles to the

gymnasium in

Castelfranco Veneto

Castelfranco Veneto ( vec, Casteło) is a town and '' comune'' of Veneto, northern Italy, in the province of Treviso, by rail from the town of Treviso. It is approximately inland from Venice.

History

The town originates from a castle built he ...

for further classes. For the next four years, he would attend Mass before breakfast and his long walk to school. He often carried his shoes to make them last longer. As a poor boy, he was often teased for his meagre lunches and shabby clothes, but never complained about this to his teachers.

[

"In 1850 he received the ]tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

from the Bishop of Treviso

The Diocese of Treviso ( la, Dioecesis Tarvisina) is Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in the Veneto, Italy. It is a suffragan diocese in the ecclesiastical province of the metropolitan Patriarchate of Venice ...

, and was given a scholarship rom

Rom, or ROM may refer to:

Biomechanics and medicine

* Risk of mortality, a medical classification to estimate the likelihood of death for a patient

* Rupture of membranes, a term used during pregnancy to describe a rupture of the amniotic sac

* ...

the Diocese of Treviso" to attend the Seminary of Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, "where he finished his classical, philosophical, and theological studies with distinction".

On 18 September 1858, Sarto was ordained a priest by

On 18 September 1858, Sarto was ordained a priest by Giovanni Antonio Farina

Giovanni Antonio Farina (11 January 1803 – 4 March 1888) was an Italian Catholic Bishop (Catholic Church), bishop known for his compassionate treatment of the poor and for his enlightened views of education; he was sometimes dubbed as the ...

(later canonized), and became a chaplain at Tombolo

A tombolo is a sandy or shingle isthmus. A tombolo, from the Italian ', meaning 'pillow' or 'cushion', and sometimes translated incorrectly as ''ayre'' (an ayre is a shingle beach of any kind), is a deposition landform by which an island becom ...

. While there, Sarto expanded his knowledge of theology, studying both Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

and canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

, while carrying out most of the functions of the parish pastor Constantini, who was quite ill. Often, Sarto sought to improve his sermons by the advice of Constantini, who referred to one of his earliest as "rubbish".[ In Tombolo, Sarto's reputation for holiness grew so much amongst the people that some suggested the nickname "Don Santo".][

In 1867, he was named archpriest of ]Salzano

Salzano ( vec, Salsan) is a town and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Venice, Veneto, northern Italy, located from Venice.

History

The area of Salzano was already inhabited in the Roman era, but it the first documents attesting its existe ...

. Here he restored the church and expanded the hospital, the funds coming from his own begging, wealth and labour. He won the people's affection when he worked to assist the sick during the cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

plague of the early 1870s. He was named a canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

of the cathedral and chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of the Diocese of Treviso, also holding offices such as spiritual director and rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the Treviso seminary, and examiner of the clergy. As chancellor he made it possible for public school

Public school may refer to:

* State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

* Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England an ...

students to receive religious instruction. As a priest and later bishop, he often struggled over solving problems of bringing religious instruction to rural and urban youth who did not have the opportunity to attend Catholic schools. At one stage, a large stack of hay caught fire near a cottage, and when Sarto arrived he addressed the frantic people, "Don't be afraid, the fire will be put out and your house will be saved!" At that moment, the flames turned in the other direction, leaving the cottage alone.dogmatic theology

Dogmatic theology, also called dogmatics, is the part of theology dealing with the theoretical truths of faith concerning God and God's works, especially the official theology recognized by an organized Church body, such as the Roman Catholic Ch ...

and moral theology

Ethics involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior.''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''"Ethics"/ref> A central aspect of ethics is "the good life", the life worth living or life that is simply sati ...

at the seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

in Treviso. On 10 November 1884, he was appointed bishop of Mantua

The Diocese of Mantua ( la, Dioecesis Mantuana) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Italy. The diocese existed at the beginning of the 8th century, though the earliest attested bishop is Laiulfus (827). ...

by Leo XIII. He was consecrated six days later in Rome in the church of Sant'Apollinare alle Terme Neroniane-Alessandrine, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, by Cardinal Lucido Parocchi

Lucido Maria Parocchi (13 August 1833 – 15 January 1903) was an Italian cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church who served as Secretary of the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office from 5 August 1896 until his death.

Biography

Luci ...

, assisted by Pietro Rota

Pietro Rota (30 January 1805 – 3 February 1890) was an Italian priest who became Bishop of Mantua, based in the city of Mantua, Northern Italy. He was given the mandate of restoring the diocese to obedience to the Pope after succeeding a popular ...

, and by Giovanni Maria Berengo. He was appointed to the honorary position of assistant at the pontifical throne

The Bishops-Assistant at the Pontifical Throne were ecclesiastical titles in the Roman Catholic Church. It designated prelates belonging to the Papal Chapel, who stood near the throne of the Pope at solemn functions. They ranked immediately belo ...

on 19 June 1891. Sarto required papal dispensation from Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

before episcopal consecration as he lacked a doctorate, making him the last pope without a doctorate until Pope Francis

Pope Francis ( la, Franciscus; it, Francesco; es, link=, Francisco; born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 17 December 1936) is the head of the Catholic Church. He has been the bishop of Rome and sovereign of the Vatican City State since 13 March 2013. ...

.

When Sarto travelled back to his hometown from Rome after his consecration, he immediately went to visit his mother. There, she repeatedly kissed his ring and said to him: "But you would not have this fine ring, son, if I did not have this", showing him her wedding ring

A wedding ring or wedding band is a finger ring that indicates that its wearer is married. It is usually forged from metal, traditionally gold or another precious metal. Rings were used in ancient Rome during marriage, though the modern prac ...

.[

]

Cardinalate and patriarchate

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

made him a cardinal of the order of cardinal priests in a secret consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

* Consistor ...

on 12 June 1893. Three days later in a public consistory on 15 June, Pope Leo XIII gave him his cardinal's red galero

A (plural: ; from la, galērum, originally connotating a helmet made of skins; cf. '' galea'') is a broad-brimmed hat with tasselated strings which was worn by clergy in the Catholic Church. Over the centuries, the red ''galero'' was restricte ...

, assigned him the titular church of San Bernardo alle Terme

San Bernardo alle Terme is a Baroque style, Roman Catholic abbatial church located on Via Torino 94 in the rione Castro Pretorio of Rome, Italy.

History

The church was built on the remains of a circular tower, which marked a corner in the so ...

, and appointed him Patriarch of Venice

The Patriarch of Venice ( la, Patriarcha Venetiarum; it, Patriarca di Venezia) is the ordinary bishop of the Archdiocese of Venice. The bishop is one of the few patriarchs in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church (currently three other Latin ...

. This caused difficulty, however, as the government of the reunified Italy claimed the right to nominate the Patriarch, since the previous sovereign, the Emperor of Austria

The Emperor of Austria (german: Kaiser von Österreich) was the ruler of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A hereditary imperial title and office proclaimed in 1804 by Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, a member of the Ho ...

, had exercised that power. The poor relations between the Roman Curia and the Italian civil government since the annexation of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

in 1870 placed additional strain on the appointment. The number of vacant sees soon grew to 30. Sarto was finally permitted to assume the position of patriarch in 1894. In regard to being named as a cardinal, Sarto told a local newspaper that he felt "anxious, terrified and humiliated".[

After being named cardinal and before leaving for Venice, he paid his mother a visit. Overwhelmed with emotion and in tears, she asked: "My son, give your mother a last blessing", sensing that it would be the last time that they would see each other.][ Arriving in Venice, he was formally enthroned on 24 November 1894.

As cardinal-patriarch, Sarto avoided politics, allocating his time to social works and strengthening parochial banks. However, in his first ]pastoral letter

A pastoral letter, often simply called a pastoral, is an open letter addressed by a bishop to the clergy or laity of a diocese or to both, containing general admonition, instruction or consolation, or directions for behaviour in particular circumst ...

to the Venetians, Sarto argued that in matters pertaining to the pope, "There should be no questions, no subtleties, no opposing of personal rights to his rights, but only obedience."

In April 1903, Pope Leo XIII reportedly said to Lorenzo Perosi

Monsignor Lorenzo Perosi (21 December 1872 – 12 October 1956) was an Italian composer of sacred music and the only member of the Giovane Scuola who did not write opera. In the late 1890s, while he was still only in his twenties, Perosi was ...

: "Hold him very dear, Perosi, as in the future he will be able to do much for you. We firmly believe he will be our successor". As a cardinal, he was considered by the time of his papal election as one of the most prominent preachers in the Church despite his lesser fame globally. In his role as a cardinal, Sarto held membership in the congregations for Bishops and Regulars, Rites

Rail India Technical and Economic Service Limited, abbreviated as RITES Ltd, is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Indian Railways, Ministry of Railways, Government of India. It is an engineering consultancy corporation, specializing in the field ...

, and Indulgences and Sacred Relics.

Papal election of 1903

Leo XIII died 20 July 1903, and at the end of that month the

Leo XIII died 20 July 1903, and at the end of that month the conclave

A papal conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a bishop of Rome, also known as the pope. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

Co ...

convened to elect his successor. Before the conclave, Sarto had reportedly said, "rather dead than pope", when people discussed his chances for election. In one of the meetings held just before the conclave, Cardinal Victor-Lucien-Sulpice Lécot spoke with Sarto in French, however, Sarto replied in Latin, "I'm afraid I do not speak French". Lécot replied, "But if Your Eminence does not speak French you have no chance of being elected because the pope must speak French", to which Sarto said, "Deo Gratias! I have no desire to be pope".Mariano Rampolla

Mariano Rampolla del Tindaro (17 August 1843 – 16 December 1913) was an Italian Cardinal in the Roman Catholic Church, and the last man to have his candidacy for papal election vetoed through ''jus exclusivae'' by a Catholic monarch.

Early li ...

. On the first ballot, Rampolla received 24 votes, Gotti had 17 votes, and Sarto 5 votes. On the second ballot, Rampolla had gained five votes, as did Sarto. The next day, it seemed that Rampolla would be elected. However, the Polish Cardinal Jan Puzyna de Kosielsko

Prince Jan Duklan Maurycy Paweł Puzyna de Kosielsko (13 September 1842 – 8 September 1911) was a Polish Roman Catholic Cardinal who was auxiliary bishop of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine) from 1886 to 1895, and the bishop of Kraków from 1895 un ...

from Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, in the name of Emperor Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

(1848–1916) of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, proclaimed a veto (''jus exclusivae

''Jus exclusivae'' (Latin for "right of exclusion"; sometimes called the papal veto) was the right claimed by several Catholic monarchs of Europe to veto a candidate for the papacy. Although never formally recognized by the Catholic Church, the ...

'') against Rampolla's election.[Bingham, John. "Secret Conclave papers show how Saint Pius X was not meant to become Pope", ''The Telegraph'', 4 June 2014](_blank)

/ref> Many in the conclave protested, and it was even suggested to disregard the veto.

However, the third vote had already begun, resulting in no clear winner but increasing support for Sarto, with 21 votes. The fourth vote showed Rampolla with 30 votes and Sarto with 24. It seemed clear that the cardinals were moving toward Sarto.

The following morning, the fifth vote gave Rampolla 10 votes, Gotti 2, and Sarto 50. Thus, on 4 August 1903, Sarto was elected to the pontificate. This marked the last known exercise of a papal veto by a Catholic monarch.

At first, it is reported, Sarto declined the nomination, feeling unworthy. He had been deeply saddened by the Austro-Hungarian veto and vowed to rescind these powers and excommunicate

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the Koinonia, communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The ...

anyone who communicated such a veto during a conclave.Luigi Macchi

Aloysius “Luigi” Macchi (3 March 1832, in Viterbo – 29 March 1907, in Rome) was an Italian Catholic nobleman and a Cardinal.

He was a nephew of Cardinal Vincenzo Macchi. In 1859, he was ordained a priest. In 1860, he was referendary o ...

announced Sarto's election at around 12:10pm.

Sarto took as his papal name Pius X, out of respect for his recent predecessors of the same name, particularly Pope Pius IX (1846–1878), who had fought against theological liberals and for papal supremacy. He explained: "As I shall suffer, I shall take the name of those Popes who also suffered".coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of ot ...

took place the following Sunday, 9 August 1903. As pope, he became ex officio Grand Master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, prefect of the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office, and prefect of the Sacred Consistorial Congregation.

Pontificate

The pontificate of Pius X was noted for conservative theology and reforms in liturgy and Church law. In what became his motto, the Pope in 1903 devoted his papacy to ''Instaurare Omnia in Christo'', "to restore all things in Christ." In his first encyclical ('' E supremi apostolatus'', 4 October 1903), he stated his overriding policy: "We champion the authority of God. His authority and Commandments should be recognized, deferred to, and respected."

Continuing his simple origins, he wore a pectoral cross of gilded metal on the day of his coronation; and when his entourage was horrified, the new pope declared he always wore it and had brought no other with him.

The pontificate of Pius X was noted for conservative theology and reforms in liturgy and Church law. In what became his motto, the Pope in 1903 devoted his papacy to ''Instaurare Omnia in Christo'', "to restore all things in Christ." In his first encyclical ('' E supremi apostolatus'', 4 October 1903), he stated his overriding policy: "We champion the authority of God. His authority and Commandments should be recognized, deferred to, and respected."

Continuing his simple origins, he wore a pectoral cross of gilded metal on the day of his coronation; and when his entourage was horrified, the new pope declared he always wore it and had brought no other with him.Confraternity of Christian Doctrine

Confraternity of Christian Doctrine (CCD) is a catechesis program of the Catholic Church, normally for children. It is also the name of an association that traditionally organises Catholic catechesis, which was established in Rome in 1562.

Rel ...

in every parish was partly motivated by a desire to save children from religious ignorance.John Vianney

John Vianney (born Jean-Baptiste-Marie Vianney; 8 May 1786 – 4 August 1859), venerated as Saint John Vianney, was a French Catholic priest who is venerated in the Catholic Church as a saint and as the patron saint of parish priests. He is oft ...

and Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronat ...

, both of whom he beatified in his papacy. At noon, he conducted a general audience with pilgrims, then had lunch at 1:00pm with his two secretaries or whomever else he invited to dine with him. Resting for a short while after lunch, Pius X would then return to work before dining at 9:00pm and a final stint of work before sleep.[

]

Church reforms and theology

Restoration in Christ and Mariology

In his 1904 encyclical '' Ad diem illum'', he views Mary in the context of "restoring everything in Christ".

He wrote:

During Pius X's pontificate, many famed Marian images were granted a canonical coronation

A canonical coronation ( la, Coronatio Canonica) is a pious institutional act of the pope, duly expressed in a bull, in which the pope bestows the right to impose an ornamental crown, a diadem or an aureole to an image of Christ, Mary or J ...

: Our Lady of Aparecida

Our Lady Aparecida - Our Lady Revealed - ( pt, Nossa Senhora Aparecida or pt, Nossa Senhora da Conceição Aparecida, links=no ) is a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the traditional form associated with the Immaculate Conception associated w ...

, Our Lady of the Pillar, Our Lady of the Cape

Our Lady of the Cape (Notre-Dame-du-Cap in French) is a title given to Mary the Mother of God in Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Quebec Canada. The title refers specifically to a statue of the Blessed Mother which is currently located in the Old Shrine.

P ...

, Our Lady of Chiquinquira of Colombia, Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos

Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos (English: Our Lady of Saint John of the Lakes) is a Roman Catholic title of the Blessed Virgin Mary venerated by Mexican and Texan faithful. The original image is a popular focus for pilgrims and is located in t ...

, Our Lady of La Naval de Manila

Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary — La Naval de Manila (Spanish: ''Nuestra Señora del Santísimo Rosario - La Naval de Manila''; Tagalog: ''Mahal na Ina ng Santo Rosaryo ng La Naval de Manila''; is a venerated title of the Blessed Virgin Mary ...

, Virgin of Help of Venezuela, Our Lady of Carmel of New York, the Marian icon of Santuario della Consolata

The Santuario della Madonna Consolata or, in its full name, the Church of the Virgin of the Consolation is a Marian sanctuary and minor basilica in central Turin, Piedmont, Italy. Colloquially, the sanctuary is known as ''La Consolata''.

It is loc ...

and the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception.

It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, meaning that it is held to be a divinely revealed truth w ...

within the ''Chapel of the Choir'' inside Saint Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

were granted this prestigious honor.

''Tra le sollecitudini'' and Gregorian chant

Within three months of his coronation, Pius X published his ''motu proprio

In law, ''motu proprio'' (Latin for "on his own impulse") describes an official act taken without a formal request from another party. Some jurisdictions use the term ''sua sponte'' for the same concept.

In Catholic canon law, it refers to a ...

'' ''Tra le sollecitudini

''Tra le sollecitudini'' (Italian for "among the concerns") was a motu proprio issued 22 November 1903 by Pope Pius X that detailed regulations for the performance of music in the Roman Catholic Church. The title is taken from the opening phrase ...

''. Classical and Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

compositions had long been favoured over Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainsong, plainchant, a form of monophony, monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek (language), Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed ma ...

in ecclesiastical music. The Pope announced a return to earlier musical styles, championed by Lorenzo Perosi

Monsignor Lorenzo Perosi (21 December 1872 – 12 October 1956) was an Italian composer of sacred music and the only member of the Giovane Scuola who did not write opera. In the late 1890s, while he was still only in his twenties, Perosi was ...

. Since 1898, Perosi had been Director of the Sistine Chapel Choir

The Sistine Chapel Choir, as it is generally called in English, or officially the Coro della Cappella Musicale Pontificia Sistina in Italian, is the Pope's personal choir. It performs at papal functions in the Sistine Chapel and in any other churc ...

, a title which Pius X upgraded to "Perpetual Director". The Pope's choice of Joseph Pothier to supervise the new editions of chant led to the official adoption of the Solesmes edition of Gregorian chant.

Liturgical reforms and communion

Pius X worked to increase devotion among both clergy and laity

In religious organizations, the laity () consists of all members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-ordained members of religious orders, e.g. a nun or a lay brother.

In both religious and wider secular usage, a layperson ...

, particularly in the Breviary, which he reformed considerably, and the Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

.

Besides restoring to prominence Gregorian Chant, he placed a renewed liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

emphasis on the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

, saying, "Holy Communion is the shortest and safest way to Heaven." To this end, he encouraged frequent reception of Holy Communion. This also extended to children who had reached the "age of discretion", though he did not permit the ancient Eastern practice of infant communion

Infant communion, also known as paedocommunion, refers to the practice of giving the Eucharist, often in the form of consecrated wine mingled with consecrated bread, to young children. This practice is standard throughout Eastern Christianity, w ...

. He also emphasized frequent recourse to the Sacrament of Penance

The Sacrament of Penance (also commonly called the Sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession) is one of the Sacraments of the Catholic Church, seven sacraments of the Catholic Church (known in Eastern Christianity as sacred mysteries), in which ...

so that Holy Communion would be received worthily. Pius X's devotion to the Eucharist would eventually earn him the honorific of "Pope of the Blessed Sacrament", by which he is still known among his devotees.

In 1910, he issued the decree ''Quam singulari

''Quam singulari'' was a decree released by Pope Pius X in 1910, concerning the admittance of children to the Eucharist. This followed a decree by the Sacred Congregation of the Council, five years before on frequent Communion.

Background

There ...

'', which changed the age at which Communion could be received from 12 to 7 years old, the age of discretion

In the canon law of the Catholic Church, a person is a subject of certain legal rights and obligations. Persons may be distinguished between physical and Juridical person, juridic persons. Juridic persons may be distinguished as Collegiality in th ...

. The pope lowered the age because he wished to impress the event on the minds of children and stimulate their parents to new religious observance; this decree was found unwelcome in some places due to the belief that parents would withdraw their children early from Catholic schools, now that First Communion was carried out earlier.[ When people would criticize Pius X for lowering the age of reception, he simply quoted the words of Jesus, "let the little children come to me".

Pius X said in his 1903 ''motu proprio'' ''Tra le sollecitudini'', "The primary and indispensable source of the true Christian spirit is participation in the most holy mysteries and in the public, official prayer of the Church."]sedia gestatoria

The ''sedia gestatoria'' (, literally 'chair for carrying') or gestatorial chair is a ceremonial throne on which popes were carried on shoulders until 1978, which was later replaced outdoors in part with the popemobile. It consists of a richly a ...

'' as was traditional. He arrived on foot wearing a cope and mitre at the end of the procession of prelates "almost hidden behind the double line of Palatine Guards through which he passed".

Anti-modernism

Pope Leo XIII had sought to revive the inheritance of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, 'the marriage of reason and revelation', as a response to secular 'enlightenment'. Under Pius X, ''neo-Thomism

Neo-scholasticism (also known as neo-scholastic Thomism Accessed 27 March 2013 or neo-Thomism because of the great influence of the writings of Thomas Aquinas on the movement) is a revival and development of medieval scholasticism in Catholic the ...

'' became the blueprint for theology.

Most controversially, Pius X vigorously condemned the theological movement he termed 'Modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

', which he regarded as a heresy endangering the Catholic faith

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The movement was linked especially to certain Catholic French scholars such as Louis Duchesne, who questioned the belief that God acts in a direct way in the affairs of humanity, and Alfred Loisy

Alfred Firmin Loisy (; 28 February 18571 June 1940) was a French Roman Catholic priest, professor and theologian generally credited as a founder of modernism in the Roman Catholic Church. He was a critic of traditional views of the interpretation ...

, who denied that some parts of Scripture were literally rather than perhaps metaphorically true. In contradiction to Thomas Aquinas they argued that there was an unbridgeable gap between natural and supernatural knowledge. Its unwanted effects, from the traditional viewpoint, were relativism and scepticism. Modernism and relativism, in terms of their presence in the Church, were theological trends that tried to assimilate modern philosophers like Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

as well as rationalism into Catholic theology. Modernists argued that beliefs of the Church have evolved throughout its history and continue to evolve

Anti-Modernists viewed these notions as contrary to the dogmas and traditions of the Catholic Church. In the decree entitled ''Lamentabili sane exitu

''Lamentabili sane exitu'' ("with truly lamentable results") is a 1907 syllabus, prepared by the Roman Inquisition and confirmed by Pope Pius X, which condemns errors in the exegesis of Holy Scripture and in the history and interpretation of dogm ...

'' ("A Lamentable Departure Indeed") of 3 July 1907, Pius X formally condemned 65 propositions, mainly drawn from the works of Alfred Loisy and concerning the nature of the Church, revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

, biblical exegesis

Biblical criticism is the use of critical analysis to understand and explain the Bible. During the eighteenth century, when it began as ''historical-biblical criticism,'' it was based on two distinguishing characteristics: (1) the concern to ...

, the sacraments, and the divinity of Christ. That was followed by the encyclical '' Pascendi dominici gregis'' (or "Feeding the Lord's Flock"), which characterized Modernism as the "synthesis of all heresies." Following these, Pius X ordered that all clerics take the Anti-Modernist oath

The Oath Against Modernism was required of "all clergy, pastors, confessors, preachers, religious superiors, and professors in philosophical-theological seminaries" of the Catholic Church from 1910 until 1967. It was instituted on 1 September 191 ...

, ''Sacrorum antistitum''. Pius X's aggressive stance against Modernism caused some disruption within the Church. Although only about 40 clerics refused to take the oath, Catholic scholarship with Modernistic tendencies was substantially discouraged. Theologians who wished to pursue lines of inquiry in line with Secularism, Modernism, or Relativism had to stop, or face conflict with the papacy, and possibly even excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

.

Pius X's attitude toward the Modernists was uncompromising. Speaking of those who counseled compassion, he said: "They want them to be treated with oil, soap and caresses. But they should be beaten with fists. In a duel, you don't count or measure the blows, you strike as you can."Sodalitium Pianum

''Sodalitium Pianum'' is Latin for "the fellowship of Pius," referring to Pope Pius V; the sedeprivationist organization with the same name refers to Pope Pius X.

In reaction to the movement within the Roman Catholic Church known as Modernism, P ...

'' (or League of Pius V), an anti-Modernist network of informants, which was much criticized due to its accusations of heresy on the flimsiest evidence.Umberto Benigni

Umberto Benigni, circa 1910

Umberto Benigni was a Catholic priest and Church historian, who was born on 30 March 1862 in Perugia, Italy and died on 27 February 1934 in Rome.

Biography

A lecturer in Church history from 1885, one year after his ord ...

in the Department of Extraordinary Affairs in the Secretariat of State, which distributed anti-Modernist propaganda and gathered information on "culprits". In Benigni's secret code, Pius X was known as ''Mama''.

''Catechism of Saint Pius X''

In 1905, Pius X in his letter ''Acerbo nimis'' mandated the establishment of the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine (catechism class) in every parish in the world.

In 1905, Pius X in his letter ''Acerbo nimis'' mandated the establishment of the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine (catechism class) in every parish in the world.[.] The catechism was extolled as a method of religious teaching in his encyclical ''Acerbo nimis'' of April 1905.

The ''Catechism of Saint Pius X'' was issued in 1908 in Italian, as ''Catechismo della dottrina Cristiana, Pubblicato per Ordine del Sommo Pontifice San Pio X''. An English translation runs to more than 115 pages.

Asked in 2003 whether the almost 100-year-old ''Catechism of Saint Pius X'' was still valid, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the soverei ...

said: "The faith as such is always the same. Hence the Catechism of Saint Pius X always preserves its value. Whereas ways of transmitting the contents of the faith can change instead. And hence one may wonder whether the Catechism of Saint Pius X can in that sense still be considered valid today."

Reform of canon law

Canon law in the Catholic Church varied from region to region with no overall prescriptions. On 19 March 1904, Pope Pius X named a commission of cardinals to draft a universal set of laws. Two of his successors worked in the commission: Giacomo della Chiesa, who became Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (Latin: ''Benedictus XV''; it, Benedetto XV), born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, name=, group= (; 21 November 185422 January 1922), was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His ...

, and Eugenio Pacelli, who became Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

. This first Code of Canon Law was promulgated by Benedict XV on 27 May 1917, with an effective date of 19 May 1918, and remained in effect until Advent 1983.

Reform of Church administration

Pius X reformed the Roman Curia with the constitution ''Sapienti Consilio

In the Roman Curia, a congregation ( lat, Sacræ Cardinalium Congregationes) is a type of department of the Curia. They are second-highest-ranking departments, ranking below the two Secretariats, and above the pontifical councils, pontifical co ...

'' (29 June 1908) and specified new rules enforcing a bishop's oversight of seminaries in the encyclical ''Pieni l'animo''. He established regional seminaries (closing some smaller ones), and promulgated a new plan of seminary study. He also barred clergy from administering social organizations.

Church policies towards secular governments

Pius X reversed the accommodating approach of Leo XIII towards secular governments, appointing

Pius X reversed the accommodating approach of Leo XIII towards secular governments, appointing Rafael Merry del Val

Rafael Merry del Val y Zulueta, (10 October 1865 – 26 February 1930) was a Spanish Roman Catholic cardinal.

Before becoming a cardinal, he served as the secretary of the papal conclave of 1903 that elected Pope Pius X, who is said to have ac ...

as Cardinal Secretary of State (Merry del Val would later have his own cause opened for canonization in 1953, but still has not been beatifiedÉmile Loubet

Émile François Loubet (; 30 December 183820 December 1929) was the 45th Prime Minister of France from February to December 1892 and later President of France from 1899 to 1906.

Trained in law, he became mayor of Montélimar, where he was not ...

visited the Italian monarch Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

(1900–1946), Pius X, still refusing to accept the annexation of the papal territories by Italy, reproached the French president for the visit and refused to meet him. This led to a diplomatic break with France and to the 1905 Law of Separation between church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular stat ...

, by which the Church lost government funding in France. The pope denounced this law, and removed two French bishops for recognising the Third Republic. Eventually, France expelled the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

and broke off diplomatic relations with the Vatican.

The Pope adopted a similar position toward secular governments in Portugal, Ireland, Poland, Ethiopia, and in other states with large Catholic populations. His opposition to international relations with Italy angered the secular powers of these countries, as well as a few others like the UK and Russia. In Ireland, Protestants increasingly worried that a proposed ''Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

'' by an Irish parliament representing the Catholic majority (rather than the ''status quo'' of rule by Westminster since the 1800 Union of Ireland and Great Britain) would result in ''Rome Rule

"Rome Rule" was a term used by Irish unionists to describe their belief that with the passage of a Home Rule Bill, the Roman Catholic Church would gain political power over their interests in Ireland. The slogan was popularised by the Radical MP ...

'' due to Pius X's uncompromising stance being followed by Irish Catholics (Ultramontanism

Ultramontanism is a clerical political conception within the Catholic Church that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope. It contrasts with Gallicanism, the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by th ...

).

In 1908, the papal decree ''Ne Temere

''Ne Temere'' was a decree issued in 1907 by the Roman Catholic Congregation of the Council regulating the canon law of the Church regarding marriage for practising Catholics. It is named for its opening words, which literally mean "lest rashly" i ...

'' came into effect which complicated mixed marriages. Marriages not performed by a Catholic priest were declared legal but sacramentally invalid, worrying some Protestants that the Church would counsel separation for couples married in a Protestant church or by civil service. Priests were given discretion to refuse mixed marriages or to lay conditions upon them, commonly including a requirement that the children be raised Catholic. The decree proved particularly divisive in Ireland, which its large Protestant minority, contributing indirectly to the subsequent political conflict there and provoking debates in the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

. The long term effect of ''Ne Temere'' in Ireland was that Irish Unionism

Unionism is a political tradition on the island of Ireland that favours political union with Great Britain and professes loyalty to the United Kingdom, British Monarchy of the United Kingdom, Crown and Constitution of the United Kingdom, cons ...

which had had strongholds in Dublin as well as Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, but existed to some extent on the entire island of Ireland, declined overall and became virtually exclusively a phenomenon of what is today Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. Furthermore, while historically both Protestant Irish nationalists

Protestant Irish Nationalists are adherents of Protestantism in Ireland who also support Irish nationalism. Protestants have played a large role in the development of Irish nationalism since the eighteenth century, despite most Irish nationa ...

and Catholic Unionists existed, the divide over who should rule Northern Ireland eventually came to almost exactly match the confessional divide.

As secular authority challenged the papacy, Pius X became more aggressive. He suspended the ''Opera dei Congressi

The Opera dei Congressi or Work of the Congress was a Roman Catholic organisation that promoted Catholic ideas and culture. It was created in 1874, and observed the positions of the Catholic Church, in particular ''Non Expedit''.Helena Dawes (2011) ...

'', which coordinated the work of Catholic associations in Italy, as well as condemning ''Le Sillon

("The Furrow", or "The Path") was a French political and religious movement founded by Marc Sangnier (1873 - 1950) which existed from 1894 to 1910. It aimed to bring Catholicism into a greater conformity with French Republican and socialist ideals ...

'', a French social movement that tried to reconcile the Church with liberal political views. He also opposed trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s that were not exclusively Catholic.

Pius X partially lifted decrees prohibiting Italian Catholics from voting, but he never recognised the Italian government.

Relations with the Kingdom of Italy

Initially, Pius maintained his prisoner in the Vatican

A prisoner in the Vatican ( it, Prigioniero nel Vaticano; la, Captivus Vaticani) or prisoner of the Vatican described the situation of the Pope with respect to Italy during the period from the capture of Rome by the armed forces of the Kingdom of ...

stance, but with the rise of socialism he began to allow the ''Non Expedit

(Latin for "It is not expedient") were the words with which the Holy See enjoined upon Italian Catholics the policy of boycott from the polls in parliamentary elections.

History

The phrase, "it is not expedient," has long been used by the Roman ...

'', which prohibited Catholics from voting, to be relaxed. In 1905, he authorized bishops in his encyclical to offer a dispensation allowing their parishioners to exercise their legislative rights when "the supreme good of society" was at stake.

Relations with Poland and Russia

Under Pius X, the traditionally difficult situation of Polish Catholics in Russia did not improve. Although Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

issued a decree 22 February 1903, promising religious freedom for the Catholic Church, and in 1905 promulgated a constitution which included religious freedom, the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

felt threatened and insisted on stiff interpretations. Papal decrees were not permitted and contacts with the Vatican remained outlawed.

Activities for the United States

In 1908, Pius X lifted the United States out of its missionary status, in recognition of the growth of the American Church.Vice-President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

Charles W. Fairbanks

Charles Warren Fairbanks (May 11, 1852 – June 4, 1918) was an American politician who served as a senator from Indiana from 1897 to 1905 and the 26th vice president of the United States from 1905 to 1909. He was also the Republican vice pre ...

, who had addressed the Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

association in Rome, as well as with former President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, who intended to address the same association.James Gibbons

James Cardinal Gibbons (July 23, 1834 – March 24, 1921) was a senior-ranking American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Apostolic Vicar of North Carolina from 1868 to 1872, Bishop of Richmond from 1872 to 1877, and as ninth ...

to invoke the patronage of the Immaculate Conception for the construction site of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception is a large minor Catholic basilica and national shrine in the United States in Washington, D.C., located at 400 Michigan Avenue Northeast, adjacent to Catholic University.

...

in Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

.

Miracles during the pope's lifetime

Other than the stories of miracles performed through the pope's intercession after his death, there are also stories of miracles performed by the pope during his lifetime.

On one occasion, during a papal audience, Pius X was holding a paralyzed child who wriggled free from his arms and then ran around the room. On another occasion, a couple (who had made confession to him while he was bishop of Mantua) with a two-year-old child with meningitis wrote to the pope and Pius X then wrote back to them to hope and pray. Two days later, the child was cured.Ernesto Ruffini

Ernesto Ruffini (19 January 1888 – 11 June 1967) was an Italian cardinal of the Catholic Church who served as Archbishop of Palermo from 1945 until his death, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1946 by Pope Pius XII.

Biography

Ruffini was ...

(later the Archbishop of Palermo) had visited the pope after Ruffini was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and the pope had told him to go back to the seminary and that he would be fine. Ruffini gave this story to the investigators of the pontiff's cause for canonization.[ Another case saw an Irish girl covered in sores taken to see the pope by her mother. When Pius X saw her, he placed his hand on her head, and the sores completely disappeared. Another case saw a Roman schoolgirl contract a serious foot disease that rendered her crippled since she was only a year old. Through a friend she managed to acquire one of the pope's socks and was told that she would be healed if she wore it, which she did. At the moment she placed the sock on, the diseased foot was instantly healed. When Pius X heard about this, he laughed and said, "What a joke! I wear my own socks every day and still I suffer from constant pain in my feet!"][

]

Other activities

In addition to the political defense of the Church, liturgical reforms, anti-modernism, and the beginning of the codification of canon law, the papacy of Pius X saw the reorganisation of the Roman Curia. He also sought to update the education of priests, seminaries and their curricula were reformed. In 1904 Pope Pius X granted permission for diocesan seminarians to attend the College of St. Thomas. He raised the college to the status of ''Pontificium'' on 2 May 1906, thus making its degrees equivalent to those of the world's other pontifical universities. By

In addition to the political defense of the Church, liturgical reforms, anti-modernism, and the beginning of the codification of canon law, the papacy of Pius X saw the reorganisation of the Roman Curia. He also sought to update the education of priests, seminaries and their curricula were reformed. In 1904 Pope Pius X granted permission for diocesan seminarians to attend the College of St. Thomas. He raised the college to the status of ''Pontificium'' on 2 May 1906, thus making its degrees equivalent to those of the world's other pontifical universities. By Apostolic Letter

Ecclesiastical letters are publications or announcements of the organs of Roman Catholic ecclesiastical authority, e.g. the synods, but more particularly of pope and bishops, addressed to the faithful in the form of letters.

Letters of the pop ...

of 8 November 1908, signed by the Supreme Pontiff on 17 November, the college was transformed into the ''Collegium Pontificium Internationale Angelicum''. It would become the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, ''Angelicum'' in 1963.

Pius X published 16 encyclicals; among them was ''Vehementer nos

''Vehementer Nos'' was a papal encyclical promulgated by Pope Pius X on 11 February 1906. He denounced the French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State enacted two months earlier. He condemned its unilateral abrogation of the Conc ...

'' on 11 February 1906, which condemned the 1905 French law on the separation of the State and the Church. Pius X also confirmed, though not infallibly, the existence of Limbo

In Catholic theology, Limbo (Latin '' limbus'', edge or boundary, referring to the edge of Hell) is the afterlife condition of those who die in original sin without being assigned to the Hell of the Damned. Medieval theologians of Western Euro ...

in Catholic theology in his 1905 Catechism, saying that the unbaptized "do not have the joy of God but neither do they suffer... they do not deserve Paradise, but neither do they deserve Hell or Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

." On 23 November 1903, Pius X issued a papal directive, a ''motu proprio

In law, ''motu proprio'' (Latin for "on his own impulse") describes an official act taken without a formal request from another party. Some jurisdictions use the term ''sua sponte'' for the same concept.

In Catholic canon law, it refers to a ...

'', that banned women from singing in church choirs (i.e. the architectural choir).

In the Prophecy of St. Malachy, the collection of 112 prophecies about the popes, Pius X appears as ''Ignis Ardens'' or "Burning Fire".

Declared the Tango "Off-limit"

In November 1913, Pope Pius X declared tango dancing as immoral and off-limits to Catholics. Later, in January 1914, when tango proved to be too popular to declare off-limits, Pope Pius X tried a different tack, mocking tango as "one of the dullest things imaginable", and recommending people take up dancing the ''furlana

The furlana (also spelled ''furlane'', ''forlane'', ''friulana'', ''forlana'') is an Italian folk dance from the Italian region of Friuli Venezia Giulia. In Friulian, ''furlane'' means ''Friulian'', in this case ''Friulian Dance''. In Friuli the ...

'', a Venetian dance, instead.

Canonizations and beatifications

Pius X beatified

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their nam ...

a total of 131 individuals (including groups of martyrs and those by recognition of "cultus") and canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

four. Those beatified during his pontificate included Marie-Geneviève Meunier (1906), Rose-Chrétien de la Neuville (1906), Valentin de Berriochoa (1906), Clair of Nantes

According to late traditions, Saint Clair (Latin: ''Clarus'') was the first bishop of Nantes, France in the late 3rd century.

Traditional account

According to the traditional account, Clair was sent to Nantes by Pope Linus, the successor of St. P ...

(1907), Zdislava Berka

Zdislava Berka (also Zdislava of Lemberk; 1220–1252, in what is now the northern part of Czech Republic) was the wife of Havel of Markvartice, Duke of Lemberk, and is a Czech saint of the Roman Catholic Church. She was a "wife, mother, and o ...

(1907), John Bosco

John Melchior Bosco ( it, Giovanni Melchiorre Bosco; pms, Gioann Melchior Bòsch; 16 August 181531 January 1888), popularly known as Don Bosco , was an Italian Catholic priest, educator, writer and saint of the 19th century.

While working ...

(1907), John of Ruysbroeck

John van Ruysbroeck, original Flemish name Jan van Ruusbroec () (1293 or 1294 – 2 December 1381) was an Augustinian canon and one of the most important of the Flemish mystics. Some of his main literary works include ''The Kingdom of the Di ...

(1908), Andrew Nam Thung (1909), Agatha Lin (1909), Agnes De (1909), Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronat ...

(1909), and John Eudes

John Eudes, CIM (french: link=no, Jean Eudes; 14 November 1601 – 19 August 1680) was a French people, French Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic priest and the founder of both the Order of Our Lady of Charity in 1641 and Congregation of Jes ...

(1909). Those canonized by him were Alexander Sauli

Alexander (Alessandro) Sauli, C.R.S.P. (15 February 1534 – 11 October 1592) was an Italian priest who is called the "Apostle of Corsica". He is a saint of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1571, he was appointed by Pius V to the ancient see ...

(1904), Gerard Majella

Gerard Majella (; 6 April 1726 – 16 October 1755) was an Italian lay brother of the Congregation of the Redeemer, better known as the Redemptorists, who is honored as a saint by the Catholic Church.

His intercession is sought for children, ...

(1904), Clement Mary Hofbauer

Clement Mary Hofbauer (german: Klemens Maria Hofbauer) (26 December 1751 – 15 March 1820) was a Moravian hermit and later a priest of the Redemptorist congregation. He established the presence of his congregation, founded in Italy, north of th ...

(1909), and Joseph Oriol

Joseph Oriol (José Orioli) ( ca, Sant Josep Oriol) (23 November 1650 – 23 March 1702) was a Spanish Roman Catholic priest now venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church who is called the "Thaumaturgus of Barcelona".

He was beatified under Po ...

(1909).

In 1908 Pope Pius X named John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of ...

a patron saint of preachers.["Chrysostom, John", ''An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church'', The Episcopal Church]

/ref>

Consistories

Pius X created 50 cardinals in seven consistories held during his pontificate which included noted figures of the Church during that time such as Désiré-Joseph Mercier

Désiré Félicien François Joseph Mercier (21 November 1851 – 23 January 1926) was a Belgian cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church and a noted scholar. A Thomist scholar, he had several of his works translated into other European languages. H ...

(1907) and Pietro Gasparri

Pietro Gasparri, GCTE (5 May 1852 – 18 November 1934) was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and ...

(1907). In 1911, he increased American representation in the cardinalate based on the fact that the United States was expanding; the pope also named one cardinal ''in pectore

''In pectore'' (Latin for "in the breast/heart") is a term used in the Catholic Church for an action, decision, or document which is meant to be kept secret. It is most often used when there is a papal appointment to the College of Cardinals wit ...

'' ( António Mendes Belo, whom the media accurately speculated on) in 1911 whose name he later revealed in 1914. Pius X also named as a cardinal Giacomo della Chiesa, his immediate successor, Pope Benedict XV.

Among the cardinals whom he nominated came the first Brazilian-born (and the first Latin American-born; Arcoverde

Arcoverde (''Green Bow'') is a municipality in Pernambuco, Brazil. It is located in the mesoregion of ''Sertão Pernambucano'' . Arcoverde has a total area of 353.4 square kilometers and had an estimated population of 74,822 inhabitants in 2020 acc ...

) and the first from the Netherlands ( van Rossum) since 1523. The consistory of 1911 was the largest number of cardinals elevated at a single consistory in roughly a century.

In 1911, the pope reportedly wished to elevate Diomede Panici to the cardinalate, however, Panici died before the promotion ever took place. Furthermore, this came after Panici was originally considered but passed for the elevation by Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

who even had considered elevating Panici's brother. In the 1914 consistory, Pius X considered naming the Capuchin friar Armando Pietro Sabadel to the cardinalate, however, Sabadel declined the pope's invitation.

Death and burial

In 1913, Pope Pius X suffered a heart attack, and subsequently lived in the shadow of poor health. In 1914, the pope fell ill on the Feast of the Assumption of Mary (15 August 1914), an illness from which he would not recover, and it was reported that he suffered from a fever and lung complications. His condition was worsened by the events leading to the outbreak of

In 1913, Pope Pius X suffered a heart attack, and subsequently lived in the shadow of poor health. In 1914, the pope fell ill on the Feast of the Assumption of Mary (15 August 1914), an illness from which he would not recover, and it was reported that he suffered from a fever and lung complications. His condition was worsened by the events leading to the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1914–1918), which reportedly sent the 79-year-old into a state of melancholy. He died on Thursday, 20 August 1914, only a few hours after the death of Jesuit leader Franz Xavier Wernz

Franz Xavier Wernz SJ (December 4, 1842 – August 19, 1914) was the twenty-fifth Superior General of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuit order). He was born in Rottweil, Württemberg (afterwards part of Germany).

Life

Wernz was the first of ...